Shintogo Kunimistu - Juyo Token

Nagasa: 23.1 cm

Moto-haba: 1.85 cm

Nakago length: 9.85 cm

Sugata: ko-buri uchi-sori tanto of hira zukuri, with mitsu-mune and narrow mi

Kitae: well-tempered itame-hada with thick ji-nie, flourishing chikei and prominent nie utsuri Hamon: hoso-suguha with deep nioi and thick nie mixed with coarse nie in places

Hataraki: hotsure yubashiri with detailed kinsuji, bright and clear nioiguchi.

Boshi: komaru with a shallow kaeri, and slightly course nie

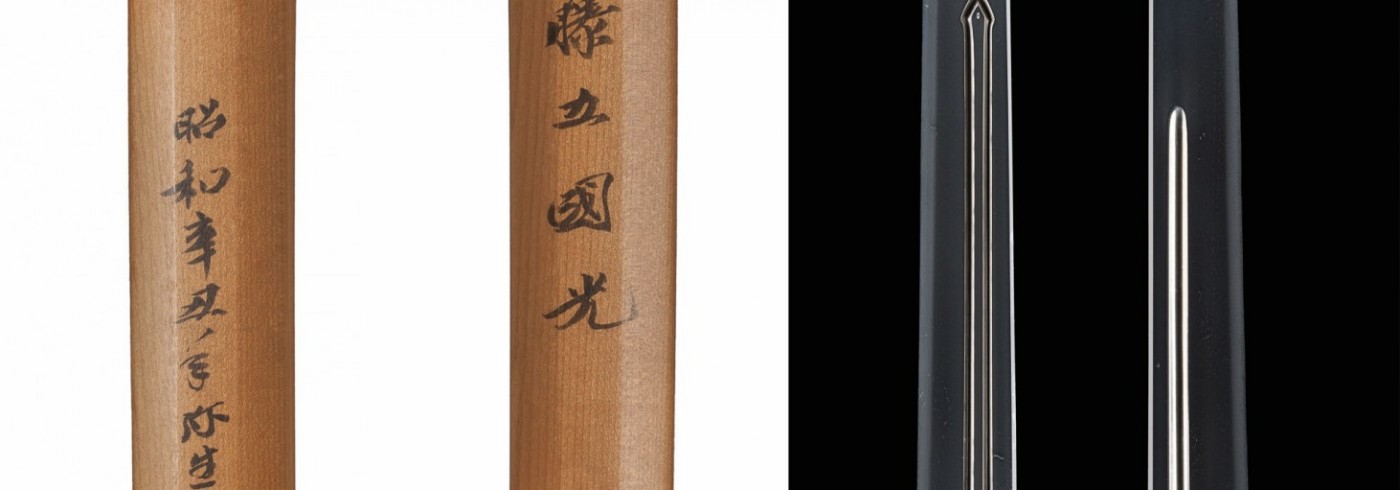

Horimono: suken on the omote with koshibi on the ura, both ending in maru do-me

Nakago: ubu, shallow saki, ha-agari kurijiri, yasurime katte sagari, one meguki-ana

Mei: “Kunimitsu” (国光)

Shintogo Kunimitsu is one of the most renowned swordsmiths. Son of Kunitsuna and pupil of Kunimune, he is the founder of what we now call the Soshu tradition; he should be also credited with nurturing his three famous pupils Yukimitsu, Norishige and, above all, Masamune, considered the best Japanese swordsmith ever.

Kunimitsu specialized in tanto and there are only few surviving tachi. His dated works range from 1293 to 1313, just after the Mongol invasions of 1274 and 1281, a period in which there was demand for efficient and durable swords. Incorporating the best features of Yamashiro and Bizen tradition, Shintogo and his pupils created blades which were extremely functional and great works of art at the same time.

This tanto well shows one of the strongest points of Kunimitsu: the steel, rich of ji-nie particles and deep nie-utsuri, a white misty formation of martensite crystals. The hamon on this blade is his favourite: a straight and elegant hoso-suguha, distinctive from the Yamashiro school where he came from, with a large number of interesting activities, typical of his works. Shintogo Kunimitsu is recognized as the supreme master of this hamon pattern, simple to design but yet extremely difficult to characterize.

As in other blades by Kunimitsu, there are simple carved decorations, different on each side: a suken and a koshibi, the second being a simplification from the first. The suken is a representation of a straight sword, typically associated with the Buddhist figure of Fudō-myōō. Shintogo always used Buddhist symbols on his works and it has been said that he may be the first smith who designed his blades to express the power of prayer: in fact, it is certainly true that the whole sword character brings us spiritual power rather than practical force.

The nakago shows the swordsmith’s typical two-character signature (niji-mei), with well-carved and healthy strokes, untouched by the mekugi-ana.

A very similar tantō is displayed in the Tokugawa Art Museum in Nagoya.

SKU: Tok-ce1